Perfume and Space: Alyssa talks about Lucio Fontana

- Perfume: an Intangible Work of Art?

- Lucio Fontana’s Spatialism

- Fontana’s Space and Perfume’s Tangibility

In my journey through art, I keep asking myself what links one art form to another, what classifies a gesture, or a perfume, as art. If the concept of art itself was deprived of the dialogue between its different declinations, it would be emptied, and it would not allow us the benefit of loving Art (with a capital A), but only one art form among others, distinct and independent. I have already spoken about the reciprocal dialogue between the arts in the article in which I introduced the concept of pan-art, but have realised that the more I think about these topics, the more my imagination is tickled by the appraisal of the concepts of perfume, perfumery and art and I find myself wandering among these thoughts!

Our society is abandoning the medieval distinction between the major and minor arts, yet, despite this, most people would not define a musical composition, a book and even less a perfume as a work of Art! Of all the senses, sight has for centuries been in charge, “monopolising” our sensory system and affecting the hierarchy of our five senses, leading us to lock our other senses in the closet.

For centuries it was believed that only sight could give true fulfilment, and that emotions deriving from employing the other senses were to be considered secondary. Touch and smell were considered secondary not only to sight, but also to taste and hearing. After all, anyone would have been pleased to taste a great dish or to listen to a musical air, but who would have been crazy enough to call an excellent and extremely soft velvet “artistic”? Who would have dreamt of displaying a perfume so evocative as to immediately bring an image to mind in a museum? No one! The tangible nature of an artefact was always associated with its artisanal rather than its artistic aspect, drastically separating these two realms which have now instead, happily, found their legitimate collocation and qualification.

Perfume: an Intangible Work of Art?

Weavers, perfumers, potters and jewellers were good or excellent artisans, never masters, but they were still capable of making products deemed beautiful to look at, useful (we can call this proto-design) and most of all long-lasting. Yes, long-lasting, as the artefact was a “possession” handed down from one generation to the next, gaining value as years went by, while still being used or worn. What about perfume? Ephemeral by nature, volatile, shapeless, how can it be made into art? Well, for centuries, sadly, it wasn’t. But if art is “knowing how to make” (artfully, indeed) with all that stems from its enjoyment, how can we not consider the technical composition, the olfactory reproduction of an event/object we have previously enjoyed with another sense to be art? The answer is in the nose, not our sensory organ, the nose is the artist/chemist who was able to make all of this possible.

Turning a memory into something tangible is possible, but if we consider that perfume is liquid and by natural law shapeless, how hard is it to make a memory tangible by using perfume? So I started asking myself about matter and the importance it has in our existence, so necessary, often neglected and, as we said, not always attributable to all things. Art has helped me, it has lent me a small part of its boundless catalogue to try and give a tangible interpretation of perfume.

Lucio Fontana’s Spatialism

Man has always reflected upon matter and will keep on doing so. First it was the “outcast” in the body-soul dichotomy, then it was investigated from a scientific point of view as it was seen as the fount of all knowledge, and later associated with modern consumer culture. In my opinion, from an artistic point of view, it was better investigated in the 1950s with the rise of the Spatialist Movement.

The Italian-Argentinian artist Lucio Fontana, known around the globe for his provocative works, signed in 1947 the first Manifesto of the Spatialist Movement. It was the passionate and prolific time of the avant-gardes when the concept of art was questioned again and again and artists thought that abandoning a time of stagnation and adapting artistic expression to the innovations of the revolutionary 20th century was necessary. Spatialists, in particular, believed that what was needed was an integral art, which included (surprise, surprise!) colour, sound, movement and space. They had not yet reached the height of sensory wholeness by including smell, as will sensorial architecture for example, but they did lay the groundwork for further reflection. Touch perceiving matter, matter collocated in space and therefore existing, space intended as a sum of absolute concepts such as Time, Light, Direction and Sound. The artists understood (or better believed it necessary to emphasise) the existence of hidden natural forces, such as rays and particles, which collaborate with all the other factors in the sensory perception of the work of art.

What would a sculpture be without the chiaroscuro effects of light on its marble? The intangible becomes fundamental for the tangible to be expressed, the work reveals the tangibility of apparently intangible elements, such as air or light, actually made by particles and molecules. So Fontana in 1958 slashed his first canvas, generating indignation and incomprehension, turning, with a gesture (time), a painting into a three-dimensional sculpture (space). Without those molecules of air, or the rays of light, the canvas would have just been the physical support of the work, but now it represents the ability to go beyond the visible, beyond matter through matter.

Fontana’s Space and Perfume’s Tangibility

Fontana’s Suspended Art, as defined in the First Manifesto of Spatialism, is therefore made up of light and molecules, shapeless substances, which shape – and give life – to things. Therefore I thought: how can you shape perfume? What do we imagine upon hearing the word “perfume”? As I said, the evocative power of smell, is powerful and extraordinary, but usually, by thinking only of the absolute concept of perfume, it is hard to imagine fields of flowers, cliffs or moments in our lives. In our mind, the drawer labelled “perfume” contains a little bottle of perfume, while the one labelled “summer” can have a sunny beach and “mum” a custard tart, as those smells remind us of those objects/moments we automatically link to others.

Perfume has a lot to do with molecules, as does the Attese (Waits) series (this is the name of the artist’s “slashed” works). We can perceive a smell thanks to odorous molecules, captured by our noses, which reach our olfactory epithelium. This is where our brain’s process of recognition and cataloguing starts. The molecules passing through the slashes in the canvas, or the earlier holes, transformed the object into artistic expression and gave it space and time. Again the molecules transformed a liquid like many others into a work of art, because without them our brain would not have picked up its unique characteristics with all the consequential emotions.

The artist of matter (painter and sculptor) called his works Waits because his gestures, whether they were slashes or holes, were never done at random. They needed days or weeks of reflection, they needed to be well pondered so the result could correspond with the concept to be transmitted. The artist-nose transforms all his creations into waits in the same way, because time influences the composition of a perfume, as, immediately after it is formulated, it can change.

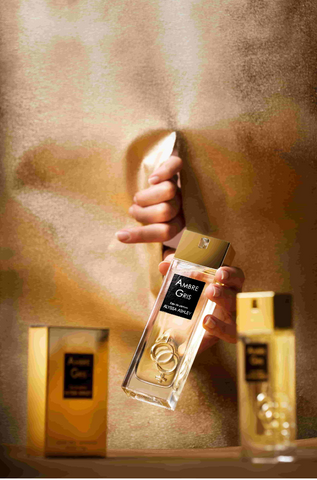

The attempt at making a perfume tangible is translated, as a homage, into a slash on a monochromatic golden canvas through which the concept of perfume is shaped, and which represents elegance and naturalness, everyday life and ostentation. This is why perfumery is an art, as it converses with them and finds in itself much of what defines the others.